Over the years, TVs, video formats and broadcast standards have advanced from Black and White to Color, from analog to digital and from low resolution signals to highly detailed images. Analog broadcast TV’s evolution to digital HDTV (High Definition Television) represented a massive improvement, particularly with full HD 1080p content. We went from around 240 lines of effective detail to over 1,000. The difference was immediately obvious.

Now there are TVs, video content, projectors and even live broadcasts of “Ultra HD TV” which can include 4K or even 8K resolution images. A 4K Ultra HD image includes four times as much detail as a 1080p HD image, with over 8,000,000 individual pixels (picture elements). An 8K image includes over 33 million pixels. And yet these resolution improvements on their own are not as impressive, subjectively speaking, as the transition from analog TV to HDTV was. On average TV screen sizes, from average viewing distances, the difference between 1080P HD and 2160P 4K is actually pretty subtle. But while the pixels began proliferating, another advancement arose that would help bring TV and display performance to the next level: HDR.

Not Just More Pixels: Better Pixels

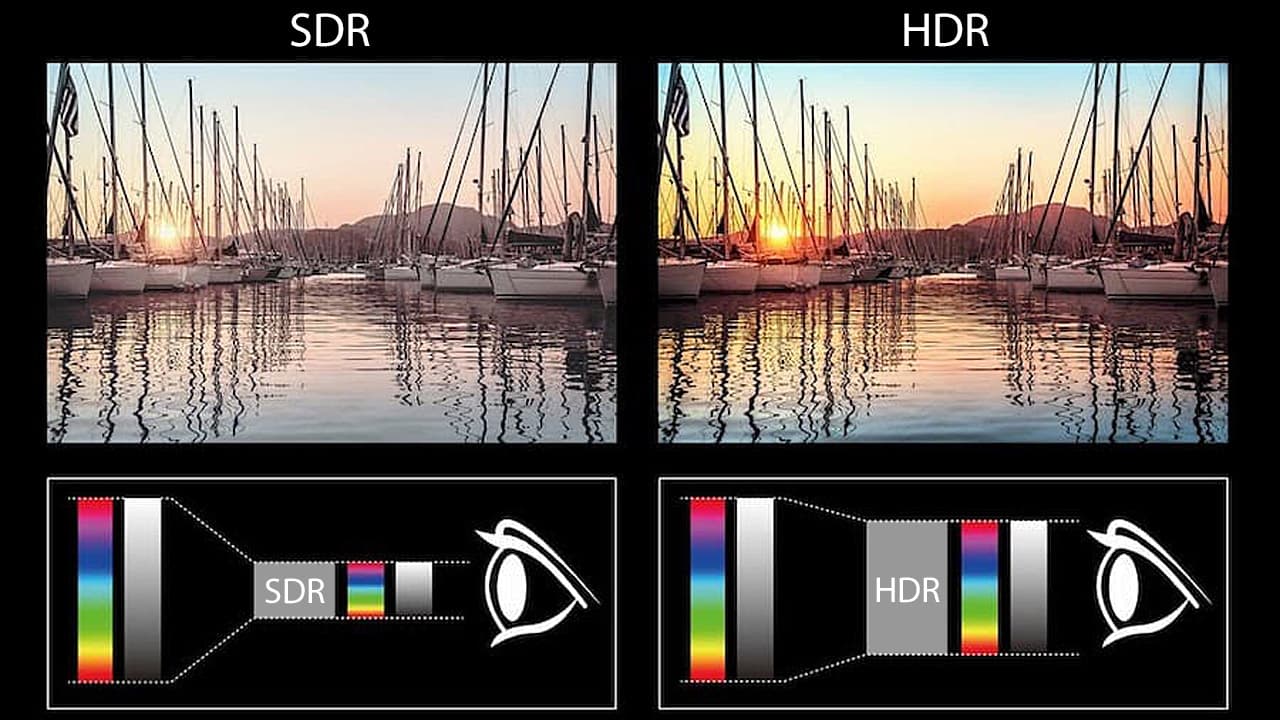

HDR (High Dynamic Range) represents the ability to capture and reproduce an image with a greater range between the blackest blacks and the brightest whites and colors. The “capture” part is done in the film and video cameras and in the mastering houses where TV shows and movies are created. The “reproduce” part is done in the display device: the projector, monitor or television. For HDR to work, it has to be present both in the content and on the display. It’s a partnership.

With the increase in dynamic range, HDR content and displays also normally (but not always) include something called WCG (Wide Color Gamut). This is an expansion in the number of different colors that a display can reproduce. As HDR is to luminance, so WCG is to color reproduction. With Wide Color Gamut support, displays are better able to reproduce fine gradations in skin tones and other colors for a more realistic presentation. By combining a greater range of brightness with a greater range of colors, display devices get closer to being able to capture what we actually see in nature.

To get an idea of what HDR is, take a look at the clouds during a bright day. You will likely notice color and brightness variations in the clouds, with dozens of shades of white and gray that flow seamlessly together. But when you look at the sky on your TV screen while watching a DVD, you will likely just see a uniform blob of mushy whitish cloud-like “stuff.” There just aren’t enough grading steps in “white” (on the TV) to display the various shades. Details in bright content are typically called “highlights.”

It’s also easy to see the limitations of dynamic range in darker scenes. Non-HDR TVs (and content) have trouble reproducing details in shadows. This is aptly enough called “shadow detail.” Once the screen gets dark enough, details in that dark just fade into the background. But HDR isn’t limited just to the darkest or brightest areas of the screen. With HDR, tropical fish look spectacular and crowded bazaars come alive with the varied color palettes of patrons and products alike.

What came before HDR is now referred to as SDR (Standard Dynamic Range). SDR content, such as older TV shows, DVDs and Blu-ray Discs, was designed for older display technologies, like CRT tube televisions. This was typically limited to around 100 nits. A “nit” is a standard measurement for brightness or luminance, equal to the light produced by one candle. Today’s LED/LCD and OLED TVs can reach a peak brightness of up to 1,000 nits, 1,500 nits, sometimes even higher. But all those nits are for naught if there is no content to take advantage of them. So HDR started making its way into new recording and mastering equipment and new standards were developed so that content creators and display makers could speak the same language.

Today HDR content is available on Ultra HD Blu-ray Discs, and in most of the popular streaming services including Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, HBO Max, Apple TV+, Disney+ and many more. Also nearly all TVs labeled as “4K TVs” or “Ultra HD” TVs include some form of HDR on board. But just because a TV includes HDR, doesn’t mean it’s going to look amazing. There are actually different flavors of HDR, some better than others. And no display device is perfect, with some “HDR TVs” a lot less perfect than others.

Static vs. Dynamic HDR

There are two basic types of HDR available: static HDR and dynamic HDR. Static HDR uses a fixed range of values for dynamic range or luminance for the entire TV show or movie. Examples of static HDR are HDR10 and HLG (Hybrid Log Gamma). HDR10 is the most common type of HDR. HLG was developed for live broadcasts and is not widely used yet. Dynamic HDR adjusts the luminance value range dynamically (usually scene by scene), based on the specific content that’s on screen at any given time. Examples of Dynamic HDR include Dolby Vision and HDR10+. Dolby Vision is very widely used today on Ultra HD Blu-ray Discs and in 4K streaming shows and movies. HDR10+ is not as common.

On a “perfect display” cable of absolute black levels and peak brightness of 1.6 billion nits (the noonday sun), static HDR would be perfectly fine. But, again, no display is perfect. And on these imperfect displays, dynamic HDR can produce more realistic, more, well… “dynamic” results.

An example would be a movie that has a bright scene of say, a couple on a beach. In such a scene, the content creators want to be able to provide details and luminance gradations in the brighter range of the luminance spectrum. This would allow the viewer to see details in the expressions of the brightly lit faces without them getting crushed (the details, not the faces). But later in the film, that same couple may be walking down a dark alley and the director wants the audience to see the eyes of a predator lurking in the shadows. Dynamic HDR metadata allows the film-makers and mastering engineers to allocate the bits (and the nits) where they need to go in order to best represent the intent in every scene.

One feature of HDR on a display device that can make or break its ability to display HDR content well is called “tone mapping.” A piece of content may be mastered for 4,000 nits peak brightness. But a particular OLED TV may max out at 850 nits and an LED/LCD set might reach its limit at 1,200 or 1,500 nits. In order to create the best, most accurate representation of the content, each TV has to “map” the luminance and color values it sees in the content to its own actual capabilities. If it didn’t you could lose a whole lot of detail in the image – on the OLED TV, any content at 850 nits all the way up to 4,000 would be “clipped” to a single shade of white. This is bad. Good HDR tone mapping scales the incoming content to match the capabilities of the TV or projector, preserving details in both the brightest highlights and the darkest shadow details, and everywhere in between.

There area a number of displays, both flat panel TVs and projectors that perform very well with HDR content. Here are our recommendations for the best HDR-capable displays currently available:

*Note: Images used are for illustrative purposes only to highlight the differences between standard dynamic range and high dynamic range content.

Rodolfo La Maestra

November 27, 2022 at 7:38 pm

Your images of SDR are greatly exaggerated dull and dark and obviously intentionally to make the HDR image pop, no mention of 8 bit vs. 10 bit vs 12 bit, PQ curve on Dolby vision, larger color gamut from BT709 to DCI/P3 and BT 2020, in addition of the wider color range obtained by 10 bit HDR increased luminance applied to every color of the particular color gamut P3 or BT2020.

No mention of the HDR limitations on otherwise excellent 4K projectors that cannot reproduce the typical luminance levels of TVs, and the variety of tone mapping proprietary implementations on displays and playback devices that make the old never-the-same-color saying of the 1980s and original ISF principles resurface again with the HDR invention.

Chris Boylan

November 28, 2022 at 7:31 pm

Thanks for your feedback. The images are exaggerated to illustrate the *concept* of HDR in a way that people can visualize on any laptop, monitor or even a phone. We can’t guarantee the quality, calibration or HDR capabilities of the displays being used to view this article so we can’t include actual SDR/HDR comparisons. The HDR version could potentially look worse than SDR on a non-HDR capable monitor as the highlights would likely be clipped. Also, the WTF articles are meant as a high-level overview on a topic, not a master class. Yes, there are many levels of additional detail that we could cover but these are not intended to be “deep dives” on the topics.